A Field Guide to Italian neo-Fascism

This article was first published on Jacobite magazine, February 1st, 2018.

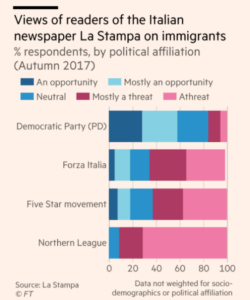

On January 7, 6,000 Italian fascists marched to commemorate the 1978 deaths of three young “comrades” during Italy’s ‘Years of Lead’ – a bloody and tumultuous period characterized by deadly clashes between communists and fascist Blackshirts. Today, the Blackshirts are, once again, striking a chord before an election in March, in a country undergoing years of technocratic gridlock. Poverty levels have doubled in the last decade and youth unemployment stands at 35 percent. Immigration has also inflamed public opinion – a recent poll published by the Financial Times revealed that only 40 percent of Italians believe in a multi-ethnic society.

The future looks bleak: Politico recently reported that 51 percent of Italians under the age of 41 would vote to leave the European Union, and 71 percent think their country is on the “wrong track.” In this unforgiving climate, fascist and identitarian movements claim to offer an alternative that will address the needs of their country and, consequently, their support is growing. For this reason, it is important to understand the three main factions on what is known as the Italian far-right.

Today fascism is commonly used as a political slur, but in Italy its meaning and heritage are more complicated. Benito Mussolini created fascist ideology, but a century later it can be hard to pin down exactly what that legacy means to his followers. At the end of the war, fascists regrouped into a new party called Movimento Sociale, and had to be reintroduced into the democratic life of the country. So, unlike Nazism in Germany, fascism in Italy was never truly eradicated. This is partly because Mussolini was – and still is – widely seen as a historically more ambiguous figure than Hitler, since Italy’s racial laws were only introduced at the behest of the Nazis following Italy’s alliance with Hitler’s National Socialist regime. Until then, Italian Jews had played an influential role in the rise of Mussolini’s National Fascist Party to power. Furthermore, Italy’s racial composition was more diverse than that of Germany, and so did not always fit the stereotype of blond, blue-eyed Aryans preferred by Germany’s racial theorists. The ambiguity surrounding fascism’s racism and relationship to the Holocaust provided a degree of space for the toleration of fascists in post-war Italy.

Now, fascist groups are again making their presence felt on Italy’s political landscape. In a stunt last month, the far-right political party Forza Nuova blockaded the office of the newspaper La Repubblica for “spreading false information.” A new law designed to curb fascist propaganda currently stuck in the Senate doesn’t outlaw their rallies and, in November, Forza Nuova organized a march of about 2,000 people in homage to Mussolini’s 1922 march on Rome.

CasaPound, another self-proclaimed fascist group, gained nine percent of the vote in the election in Ostia, a previously unthinkable result for such a marginalized movement. Forza Nuova and CasaPound are the largest self-defined fascist organisations in the country, but their views about what that period in history means to their movements differ so greatly that they refuse to associate with one another. This raises perplexing questions about what it means when analysts say that fascism is rising in 21st century Italy.

Identitarianism, on the other hand, is best understood as a separate category altogether. Generation Identity is a pan-European group of young people seeking to defend Europe against the perceived threats of Islamisation, globalisation, and the erosion of European identity. In the ‘Understand the Facts’ section of its website’s homepage, the movement explicitly rejects both Nazi and fascist associations, stating that, “Generation Identity does not provide a platform for any kind of national-socialist or fascist groups or views.” Despite overlapping concerns regarding nationalism and identity, the values of fascism and identitarianism do not always coincide. These groups merit sober comparison if we are to understand what fascism and identitarianism mean in the political context of the country that introduced fascist ideology into the world.

Ethnicity

Ethnic identity is perhaps the most contentious topic in debates about what these movements stand for. Forza Nuova, the most traditional fascist group, only supports ethnic Italians. When asked if Forza Nuova would accept Africans, or even more controversially for fascists today, Jews into their ranks, Luca Leardini – Forza Nuova’s organizer in Veneto – said: “We want to avoid accepting them because of the system that there is in place where Africans are intended to replace Europeans, and how many Jewish people appear to be behind this system.” He then appeared to equivocate a bit by arguing that Africans are also victims of the ‘system,’ and that not all Jews are to blame. However, when asked for his thoughts on the purported Jewish conspiracy, he asked abruptly: “What is Soros’s origin?”

The entrance to Forza Nuova’s office in Veneto, saying: ‘Honour to the fallen comrades.’ / Alessandra Bocchi

Forza Nuova’s focus on Italians can be inconsistent; asked if Europeans not of Italian origin would be accepted into their movement, a spokesperson said: “Europeans can integrate into Italian society, but non-Europeans generally cannot.” Their position on Nazism slides between studied ambiguity—“That’s in the past and we deal with the present” — and outright evasion — “Millions of people died making the pyramids too, but I don’t see anyone saying: ‘Let’s dismantle the pyramids, or let’s worry about what the Egyptians did at the time.’”

CasaPound, in contrast, despite also defining itself as “fascist,” does not place the same ideological emphasis on ethnicity. It claims to aspire to the Italian fascism that existed before the Nazi alliance and the subsequent introduction of racial laws. As Simone Di Stefano, recently elected head of CasaPound, explained in an interview: “We accept immigrants into our movement, including Africans and Asians, and have no problems with Italian Jews.” He added: “The Jewish people in Italy helped the fascist party rise to power … We acknowledge that the introduction of racial laws in 1938 was a mistake.”

The main desk at the Forza Nuova office in Veneto. / Alessandra Bocchi

This uncertainty around matters of race has produced some unintentionally comical moments. In response to an embarrassing controversy in which she mistook Samuel L. Jackson and Magic Johnson for idle migrants, the famous Italian model and CasaPound activist Nina Moric – herself an immigrant of Croatian origin – announced that she had agreed to invite an African migrant to live in her home for a week as part of a reality TV show. For this she would be paid $250,000, which she claimed she would use to “help more Italian families,” and her participation in the show would demonstrate that “I am not a racist person” and that “never in my life have I made distinctions based on race.” Immigration controls, she went on, “should be about protecting our towns – skin color is not important at all.” Echoing this slippery distinction, Di Stefano stated: “There is a difference between accepting some immigrants and encouraging the replacement of the Italian population.”

The Generation Identity position on ethnicity is distinct from both Forza Nuova’s radicalism and CasaPound’s professed neutrality. They focus on “ethnocultural identity,” in which both ethnicity and culture play a defining role. “It’s not about race; it’s about the community and culture that you inherit through your surroundings as well as your ancestors,” said the head of Generation Identity in Italy, Lorenzo Fiato. He clarified that the movement wouldn’t accept Africans because its purpose is to defend the identity of people it sees as disenfranchised: Europeans without a migratory background. Fiato added that he didn’t have a problem including European Jews in the movement, so long as they are non-religious. And because the ethnicity of Italian identitarians tends to be defined as ‘European Mediterranean,’ they wouldn’t necessarily define themselves as strictly or exclusively “white” given the darker ethnic composition of the country. “It’s not about the colour of your skin; it’s about lineage,” Fiato said. However, when the candidate for Lombardy Attilio Fontana made the controversial claim about defending the “white race,” many on the right jumped to his defense, showing this form of identity is growing among Italians who contrast themselves with African migrants.

Tradition

Tradition lies at the heart of these movements. Forza Nuova’s motto is: “Order in the Midst of Chaos.” It largely defines tradition in terms of Catholicism, and opposes same-sex civil unions and abortion rights. Forza Nuova’s notion of tradition harks back to the fascist era; posters of Mussolini replete with fascist mottoes and symbols cover the walls of their Veneto offices. The sense of nostalgia is overpowering, as if history ended with WWII and it is FN’s duty to bring it back. Their library is filled with books detailing the problems of modernism, Zionism, and liberalism. Some of their activists make Roman salutes as a symbol of fascist patriotism, though this is often confused with the more strict Nazi salute: the two can overlap, but are not necessarily understood as the same. Forza Nuova organiser Luca Leardini said: “We take what is positive about fascism, and leave the negative aspects behind.” But it remains unclear whether they see any negative aspects at all, Adriano da Pozzo, co-ordinator for Forza Nuova in Central Italy, explained: “For example – the fascist hymn ‘Little Black Face’ was inspired by a black Ethiopian girl the fascists wanted to bring back to Italy at the time of the invasion of Ethiopia to offer her a dignified life. But a black face has a completely different meaning to Italians today.” He was, of course, referring to what they see as the ethnic replacement of Italians by largely African migrants. Tradition for the fascists of Forza Nuova means looking to the past for today’s ideological inspiration – a combination of Catholic, nationalist, and fascist ideologies, all of which, in their view, stand in opposition to the “cancer” of modernism.

A girl holds a sign during the march on Rome on the 4th of November saying: ‘Everything for the fatherland.’ / Alessandra Bocchi

CasaPound, which views tradition as an evolving concept rather than as an antidote to modernity, combines progressive support of same-sex civil unions and abortion with a radical form of nationalism. They claim to be in favor of democracy, although their name was inspired by Ezra Pound, the expatriate poet and critic who, angered by usury and capitalism in the United States, fled to fascist Italy and declared his ambiguous support for Adolf Hitler, defining him as a “saint” who “ruined himself” with anti-Semitism. CasaPound’s more modern approach to the past and its rejection of racial ideologies has meant it is less stigmatized by the media. On several occasions, its representatives have been invited onto mainstream Italian TV channels like LA7, and debated the well-known left-leaning Italian-Jewish journalist Enrico Mentana. CasaPound is also largely a secular movement, which can put it at odds with the strict Catholicism professed by Forza Nuovo.

It’s important to note that fascism was not an avowedly religious ideology. Its main intellectual proponents and forefathers, including Julius Evola and Mussolini himself, were anti-Christian. So religion has always been a contentious topic for fascists: Does religion or the nation come first? Should tradition be based on the order understood by the Christian faith, or the Roman and Greek paganism which made ancient civilizations great? Fascist ideologies can contain several internal inconsistencies, which can lead their various adherents to adopt seemingly contradictory positions. Overall, its main intent is to defend “the nation”, in all its totality and history.

Generation Identity claims to have a more nuanced perspective on the past, neither defining themselves as fascist nor anti-fascist. Lorenzo Fiato calls modern-day fascists “nostalgic”; they look to the early 1920s for solutions to the problems of modernity. “In reality, fascism and nationalism are also modernist concepts. They came out of Jacobinism, so they are not strictly traditionalist,” he said. Generation Identity’s view of tradition is complex, and almost impossible to define neatly. Their position on women’s place in society, for example, veers between heroic descriptions of Sparta’s female warriors to more traditional views of women in domestic roles. “Women’s role cannot be defined in a monolithic way,” one of their female activists has said. They consider themselves to be irreligious, but they also oppose secularism and atheism, proposing instead a form of “spirituality” which can veer from Paganism to Christianity.

Two young activists of Generation Identity in their main office in Rome. / Alessandra Bocchi

Organisation and Outreach

Forza Nuova represents the fascism of the 1990s, whose members, many in their 40s and 50s, wear dark clothes. But they also have a youth division called ‘Lotta Studentesca’ (‘Student Fight’) which seeks to appeal to the anger and rebellious instincts of disaffected young people. It recruits from high schools and universities, and adopts a different kind of aesthetic – less fascist Celtic crosses and more Greek fighters. One ex-member, now in his 20s, said: “When I was in school they were attractive because they were eccentric and radical.” But Forza Nuova also has a plan to appeal to struggling families. “Solidarietà Nazionale” (National Solidarity) is a programme intended to help Italians in need – they claim to organize lunches and distribute food to Italians, regardless of political ideology. Andrea Visentin, head of Forza Nuova in Veneto, said: “I gave food to a man who had Che Guevara tattooed on his arm, and after some time he asked me if he could join us, amazed that his views had changed so much.” At night, Forza Nuova members organize patrols in cities like Mestre, which used to be affluent but is now disfigured by crime, drugs, and prostitution, which they say are managed by immigrant gangs. While walking at night, one could only see the Forza Nuova activists and other gangs of people, whose identity was hard to verify, around the city. One boy waiting to enter his apartment said it wasn’t safe to walk the streets alone.

CasaPound was born out of squatting buildings among working-class families in Rome, and then spread throughout other downtrodden areas of the country. Their appeal rests on their so-called “Fascism of the Left” by providing Italians in need with shelter, food, and community. In areas like Tiburtino III on Rome’s periphery, CasaPound posters can be found which read: “Once we were communists, now we have CasaPound helping us defend our homes.” Swathes of working-class areas of the country, which used to be strongholds of the Communist Party or the Democratic Party (PD), have sometimes turned to CasaPound for help. The movement can now attract as many as 10,000 people to their rallies, and its membership far outnumbers that of Forza Nuova. They too have a youth division called ‘Blocco Studentesco’ (‘Student Block’) designed to appeal to young, alienated teenagers in search of a cause for which they can fight. CasaPound says it wants to transcend the dichotomy between left and right. Their appeal largely lies in offering a working-class version of fascism responsive to modern needs.

A young activist of Generation Identity in Rome saying: ‘Let’s protect our civilization’ and ‘Defend Europe / Alessandra Bocchi

Generation Identity, in contrast to both Forza Nuova and CasaPound, is an exclusively youth-based movement, which has no intention of entering politics. “We would put ourselves on the side, as a sign of selflessness, to let young people pave the way for our movement when we get older; our intention is to awaken the young generation,” said Francesco Piane, the 24-year-old head of the Rome division. He talks about restoring values of honor, loyalty, and honesty to a generation that he says is disenchanted with the legacy of the ‘68ers, better known as the “baby-boomers.” Generation Identity makes videos to appear both tragic and heroic to attract today’s youth to their movement. “The video made by the French identitarians is what first made me want to join the movement; I could relate so closely to what they were saying,” said Fiato. That video, entitled “A Declaration of War From the Youth of France,” shows young people denouncing the values of their parents’ generation: “Our generation are the victims of the May ‘68ers who wanted to liberate themselves from tradition, from knowledge, and authority in education. But they only succeeded in liberating themselves from their responsibilities.” This message strikes a chord with millennials, who now find themselves with few job prospects in an increasingly alienating society. Generation Identity’s membership in Italy is now in the hundreds, whereas it has grown to around 2,000 across the whole of Western Europe.

A popular saying in Italy is, “Things were better when they were worse” – a paradoxical admission of past mistakes combined with nostalgia. Fascism, as a 1920s ideology, belongs in history books. But, at a time of mass immigration and increased economic hardship, some of its key tenets are being disinterred and are finding a new audience among Italians disenchanted with globalisation and technocratic administrations stained by corruption scandals. Neofascist and identitarian doctrines of various kinds promise a restoration of pride, self-confidence, and dignity to what they define as “our people.” But for these movements, the definitions of who their people are and what kind of tradition should be restored vary so much that each is willing to fight its own battle.

CasaPound headquarters in Rome, showing their flag of an Arrow Turtle and the Syrian flag representing Bashar al-Assad. / Alessandra Bocchi